Arinjoy Sen, Architectural designer & Artist, London

Hey, can you start by introducing yourself and tell us a little bit about what you do?

I’m Arinjoy. I work as an architectural designer in London, while exploring my interests and research through an arts-based practice. I look at contested landscapes, citizenship, migration, narrative, and spatial justice in my practice, primarily through the medium of drawing. I recently exhibited my work at the Venice Architecture Biennale 2023 as part of the curator’s Special Projects: Guests from the Future, which was an incredible experience. My work involves different disciplines, but I’m closest to being a spatial practitioner.

What’s a spatial practitioner?

It basically means applying the theories of architecture in ways that don’t entail “building a building”. So, a cartographer can be considered a spatial practitioner. It’s taking what you learn within the field of architecture and applying it in more flexible ways. But I’m not technically allowed to call myself “a spatial practitioner” yet.

But that’s what you’re working towards?

Yes. And also my art.

"I tell stories of people, identities, places and myths, while exploring the spatial dimension of the pictorial or visual plane."

Amazing. You’re someone I think of as working in an interdisciplinary space, even though architecture is seen as such a specialist pursuit. How would you describe what you do?

I don’t think architecture should be seen as specialist – I’ve always found it to be at the nexus of lots of disciplines, because that’s how I was taught it. I think architecture in general can be seen as akin to that of a curator – organising, and taking care of space that is informed by context, purpose, narrative, and audience.

This brings me to my own practice. I imagine my role as acting in a similar way to a storyteller. Even though my practice is quite an interdisciplinary and art-based one, the projects that I have worked on are actually always heavily based on deep and often investigative research. This is what I’ve learnt from my education and is something that I am not able to leave behind as a methodology. So in that sense, I see myself as a narrative practitioner. I tell stories of people, identities, places and myths, while exploring the spatial dimension of the pictorial or visual plane.

When you put it like that it sounds a lot less abstract. People commonly identify architects with a very glamorised, hyper-individual authorship. How do you feel about this stereotype?

I think that it’s an idea that we need to push back against. It overemphasised the most powerful person in the room at the cost of the group. And architecture has historically been a very privileged, academic discipline. So, this stereotype reinforces inequality within the profession. We are still in the process of recovering architecture from this status – of exclusive, and dominated by people of privilege – and opening it up to people from a wider set of backgrounds. And we still have a long way to go. When faced with a ‘starchitect’, as we call them, people start thinking, “It’s fine for me to work for free, because I’m learning from a genius.” But, finally, we’re starting to realise that that’s not how shit works. It’s hard though. When I meet someone whose work I admire, who I consider a genius, I’m already wanting to work with them at any cost. But when the whole of society positions someone as a genius, yeah, it can invite exploitation and crazy overtime work. Because people will do anything for that stamp.

"Collective endeavours are always stronger than individual ones."

You could read the idea of interdisciplinary work as a collaboration between disciplines. Do you think that interdisciplinary work invites a more collaborative ethic?

Yeah. To an extent. You can be interdisciplinary and still try to do everything on your own. It’s within the person to embody or practise a collaborative ethic. I believe that, interdisciplinary or not, collaboration is the way forward. A collaborative work ethic opens up so many more possibilities. Collective endeavours are always stronger than individual ones. It’s not necessarily easy but it’s definitely worth it.

Can you tell us what your daily routine is like, and what you have been up to over the past few months?

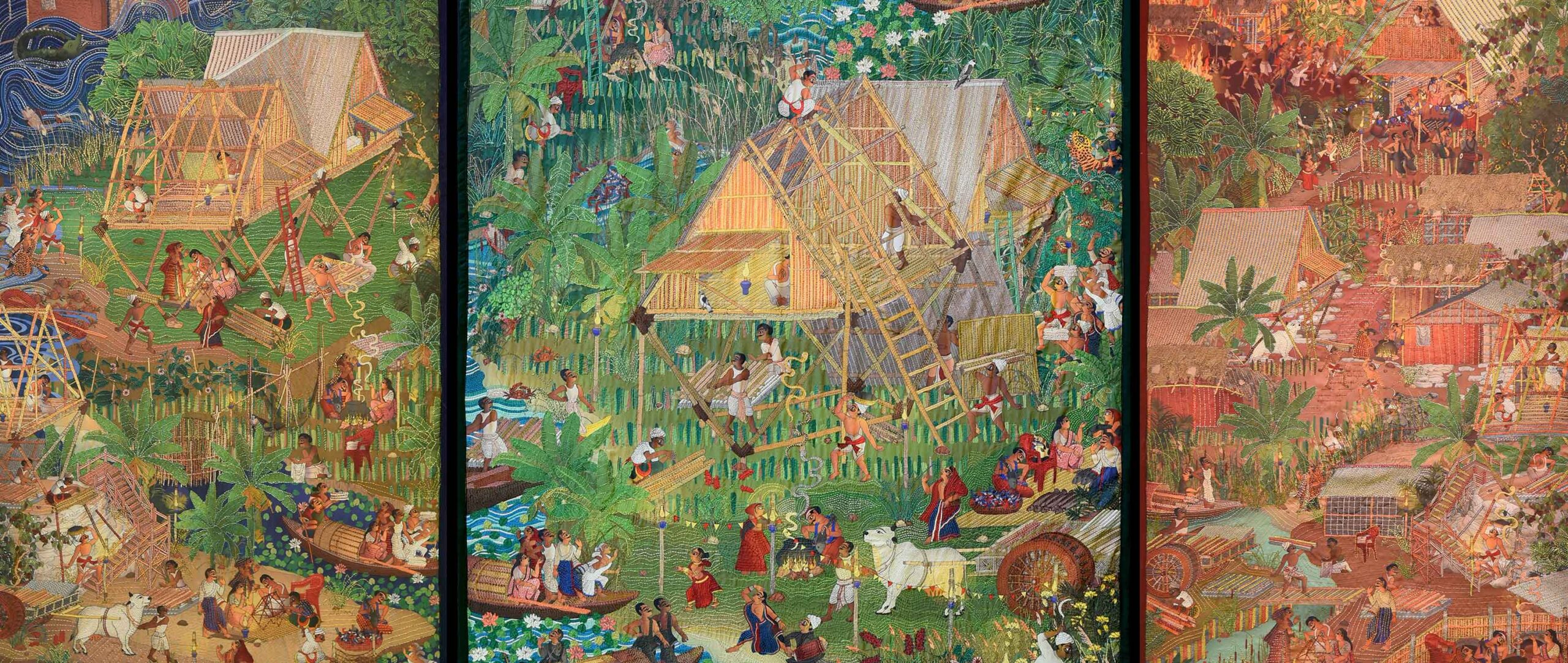

I’m perpetually a bit all over the place (laughs) but I don’t think my daily routine is very interesting. I have a full-time job in a commercial architecture practice, which takes up most of my time. My own work starts after that. I recently completed a triptych of short films that I had made for the V&A Friday Lates — based on my exhibit, a triptych of hand embroidered tapestries titled ‘Bengali Song’ at the Venice Biennale. I’m currently working on a piece of painting that deals with themes of identity, myth and temptation, and a capsule collection of clothes that is trying to explore hybrid identities and the idea of masculinity that evolved historically through South Asia. Finally, I’ve just started discussing a collaborative project with a textile artist based on the theme of lost goddesses.

How do you find London as a young artist?

I love working in London. I grew up in Kolkata — a huge city — so I appreciate a certain level of chaos. Nowadays I get a lot of inspiration from London itself. When I first moved to the UK I lived in Manchester and then Liverpool, but I always knew that I wanted to end up in London because it is such a cultural hub. At the same time, I need to learn how to not get too affected by the pace of cultural production around me. Everything moves so fast and it can be anxiety-inducing when you feel like you can’t match what you’re seeing around you.

How do you negotiate creativity and work ethic?

Architecture is known for its notoriously bad work ethic, in the sense that it is expected of us to do a significant amount of unpaid overtime. This is a real problem with the industry. At the moment my day job is time-consuming and often not intellectually stimulating enough, which is good because I don’t want to get carried away or too invested in that work. More often than not, your views and opinions won’t be taken into consideration at the end of the day, so it’s a fight not always worth fighting for a number of reasons. And, look, my bills are paid, I’m living in London. I have access to office resources – amazing computers, amazing softwares. I can workshop there. I can make stuff. I have a community of creatives that I can tap into if I need. If you think about what you are getting out of it, it’s a lot easier to deal with the disenfranchisement. And it means I have to look for fulfilment not in my day job, but in the area that I ultimately care about, which is my art.

Seems like you’ve got it figured out. Can you tell me about some challenges you have encountered in your work?

One of my biggest challenges has been overcoming the idea that architecture is a tool used to solve problems. It’s implicit to the way you’re taught architecture. That starts very early on. And it bigs you up as a designer and gives the project more importance than necessary. They say that “every line you draw needs to be justified.” Very rarely can you justify a design by saying “because it’s beautiful”. Of course, this comes into play when you’re selling to a client. But, inevitably, it also takes away the inherent subjectivity that will also play a part in your decision-making. In quite an inorganic way, you’re expected to constantly provide a rational foundation to every choice you make. Parents will more happily let their kid study architecture, because of its association of high-logic and rationality, than, perhaps, something like fine art. But the need to justify everything in your work is so incessant. It’s very difficult for me to be an artist because of it. I am so envious of people who can express themselves freely and spontaneously. The need to self-justify can create a real lack of self-confidence, and can push against a free artistic impulse that belongs in architecture alongside rational science.

When did you start confronting this idea? Was there a lightbulb moment?

Sort of. When I had just started my postgrad in 2019, I decided to start a project to address the socio-political situation in India and Kashmir. At the time, India and Pakistan were on the brink of war. The government of India was and still is exercising an increasing colonial, oppressive occupation of Kashmir that led to the Shaheen Bagh protests across the country and worldwide. I was emotionally and psychologically quite affected by this – isolated as well. No one around me in London knew what was going on or was talking about it, and before long we were going into lockdown, and I was stuck in the UK. So I decided to address the situation in Kashmir in my project. I wanted to solve the socio-political and economic issues while addressing the current situation. I was going round in circles for months. Eventually, I accepted that my work couldn’t ‘solve’ this problem. But up until this point, I had worked to the sole effect of presenting a problem with a solution. To my mind, that was what architecture was. But I had to re-evaluate. And so, instead, I tried to use my project to tell the story of Kashmir and bring to light the narratives constantly at risk of being erased. And that ended up defining a lot of what my work is now.

Your work is so rooted in narrative – like you said earlier, you identify as a narrative practitioner. So that must have been a pretty pivotal moment.

For sure. The other challenge that I often face in my work, and I think this is something I share with a lot of people of colour, is addressing and exploring non-western cultural and political landscapes. This is a challenge that I faced throughout my career, especially in the predominantly white male occupied spaces of the art and architecture world. At uni I felt as though some of my tutors and peers were not well-equipped to understand or be perceptive to the contexts, narratives and identities that I was trying to explore. This is something that has made me and other students of colour that I know feel quite isolated or alienated, especially when you are trying to address and situate work in non-western landscapes or challenging western canons.

Do you have any advice for people starting out in architecture, or similar work to you? People who might be facing the same sort of challenges?

First and foremost, believe in yourself. I know it sounds cheesy but it takes effort. Especially if you are trying to do something different, and don’t have the support you need around you. It took me a long time to reach a point where I had enough faith in myself to follow through with a project. I still struggle with that. Also, make friends and seek out help. Don’t be afraid to get in touch with people whose work you might relate to or you think might be able to help or offer advice, even if they are beyond your social, academic or professional bubble. Doing this has helped me so much. I wish I had done it earlier. As well, making friends whose opinion or work you respect helps because you can discuss your ideas and learn from them. Finally, if you can, use your work to promote the things that you believe in and have solidarity with one another.

Ok, that seems like a good point to end on. Arinjoy, what drives you?

Curiosity and things that I believe in.

Hero Image: ‘Bengali Song’

Image 01: Arinjoy Sen with ‘Bengali Song’

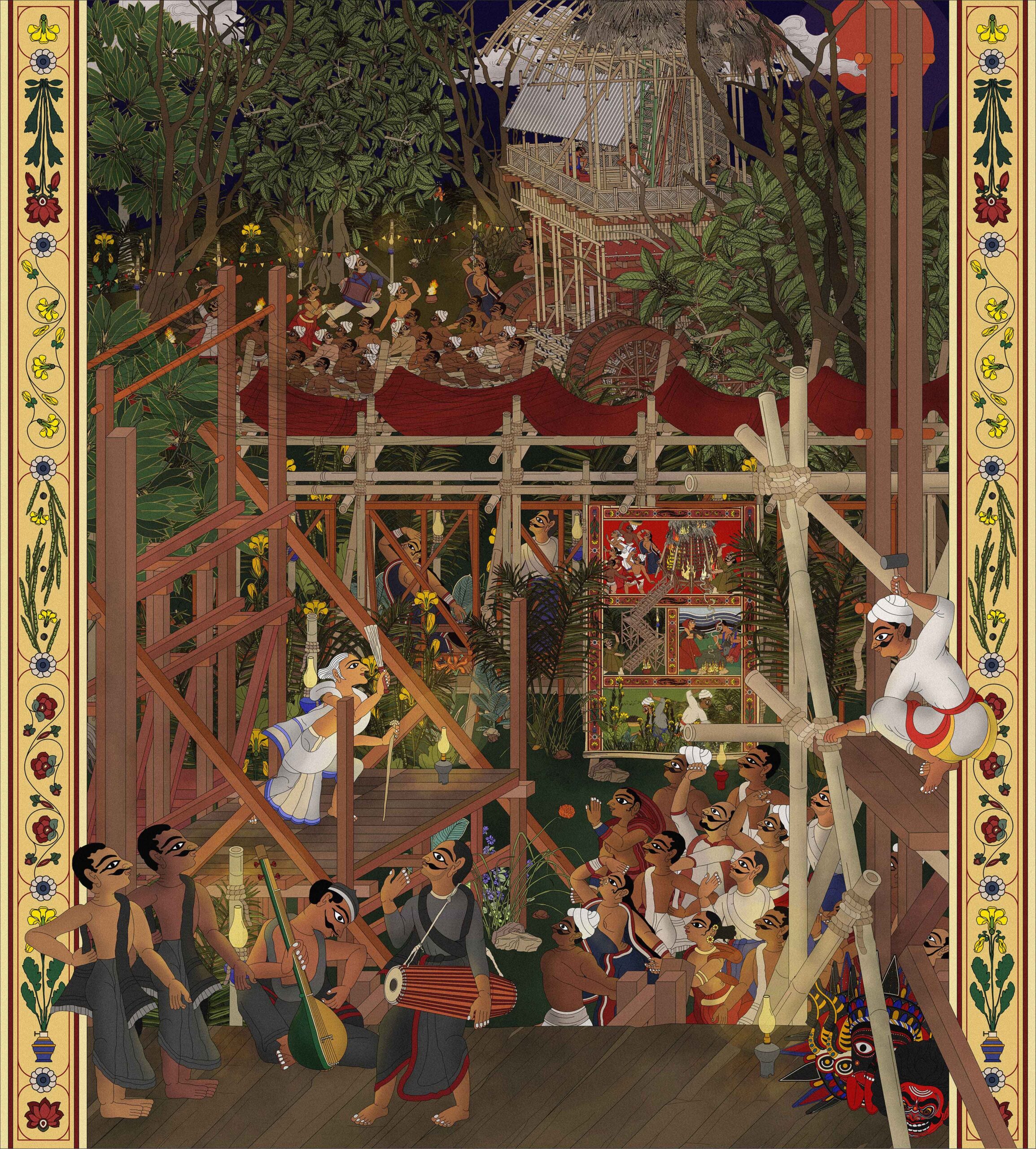

Image 02: ‘Theatre of Resistance’

Image 03: ‘The Carnivalesque as Counterculture’

LATEST THAT MAY INTEREST YOU